GHOST WORLD

ARTICLE ISSUE TEN / 2017

Tate Britain’s autumn retrospective on sculptor Rachel Whiteread provides a timely opportunity to celebrate her prodigious body of work — and to re-examine how her castings of objects and buildings have infiltrated our attitudes to space and place.

Rachel Whiteread is an artist rooted in place. That may sound contradictory, given that she’s travelled the world to create her monumental public sculptures, from Vienna to New York to Norway. But wherever Whiteread finds herself, she uncovers the intricacies of her location — intricacies which, in turn, inform the concepts behind her works. Whether she’s creating rubber replicas of abandoned mattresses, inspired by the grittiness of East London life, or looking to New York’s iconic skyline for 1998’s Water Tower, she has always been carefully considered about context.

We should, perhaps, expect nothing less from an artist who has such a visceral engagement with space; one whose most iconic works have turned empty, everyday spaces around the planet into something that is — quite literally — concrete.

Looking back across Whiteread’s career, it’s impossible to ignore her connection with the YBA’s (the catch-all term given to the group of young British artists who began exhibiting around 1988.) In many ways, Whiteread is a classic YBA; a contemporary of some of the most famous (Damien Hirst, Tracey Emin) and friends with others (like Gary Hume). And Ghost’(1990), her first room cast, was bought by collector Charles Saatchi, and shown in the Royal Academy’s seminal Sensation exhibition (the show that is often credited with launching the YBA phenomenon.)

And yet, in other ways, Whiteread breaks the mould. She loathes the controversy that sometimes follows her work, and (unlike some of her high-profile contemporaries) her practice has remained remarkably consistent over the years. ‘Since my career started, I’ve basically done the same thing over and over again.’ she told the Independent in 2010. ‘I mean that in a positive way. I think that’s what good art is – the same process and research, but refining your strategy.’

It’s been three decades since Rachel Whiteread graduated from the Slade School of Art. Produced the same year, Closet (1987) — a casting of a wardrobe interior, covered in black felt — was the first indication of her focus. It was included in her first solo exhibition, alongside 1988’s Shallow Breath (a cast of the underside of the bed that the artist was born in.) Viewed as a response to the death of Whiteread’s father, Shallow Breath deals with loss and memorialisation, solidifying the ephemeral space surrounding an object of personal importance. The new object, the cast, becomes a reminder (in every sense) of what is no longer there.

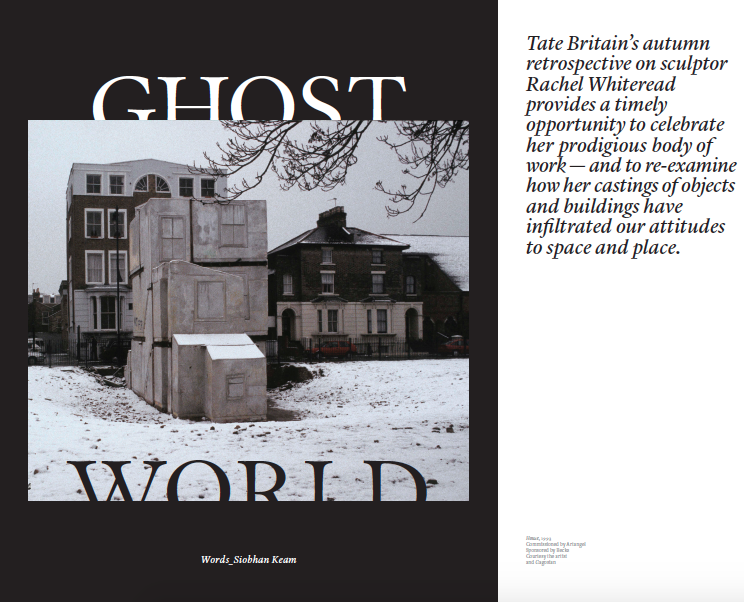

After Closet and Shallow Breath, Whiteread’s work would rapidly grow more ambitious in scale. Ghost (1990) saw her cast an entire room, from 485 Archway Road — an abandoned North London house, earmarked for demolition as part of a road-widening project. Created from a room similar to the one she grew up in (Whiteread’s family moved from Ilford to London when she was seven years old), the chosen object — and, in this case, the location of the building it was cast from — form an integral part of the work. ‘

Ghost took two years to produce, from conception to completion. And it was, in many ways, a precursor to the breakout moment that would push Whiteread into the mainstream spotlight.

Unveiled in 1993, House quickly became one of the most controversial public sculptures in Britain. It was created by casting an entire house in Mile End — a house, like the one on Archway Road, that was scheduled to be demolished.

Like Ghost, the project’s location is important. Whiteread has spent much of her life in East London, and currently lives and works in Hackney. Those connections mean that the work was not only an impressive feat of dogged determination and planning (just try to imagine, if you can, the logistics of casting an entire house), but also a considered memorial to the way the area’s neglected Victorian housing stock was disappearing in the name of regeneration; in the case of 193 Grove Road, it was the last, stubborn hold-out from a terrace razed to create a new park.

House won Whiteread the Turner Prize in 1993; that same day, Tower Hamlets Council voted to demolish it. She welcomed the public conversation and engagement surrounding both the project’s creation and destruction. (Soon after it opened, the words ‘Wot for?’ appeared, scrawled on the piece’s side; before long, another piece of graffiti retorted ‘Why not?’ ) The house drew thousands of visitors a day, whilst its intransigent former inhabitant, ex-docker Sydney Gale, became a tabloid regular. Simultaneously with announcement of her victory at the Turner Prize, Whiteread was awarded the more dubious honour of Worst British Artist by the K Foundation.

In a sense, the controversy forms another aspect of the work, overtaking the original piece with the media and public interest that surrounded it. Linsey Young, Tate Britain’s curator of Contemporary British Art and co-curator (with Ann Gallagher) of the upcoming Whiteread retrospective, has tackled the challenge of showing the now-demolished House, and other seminal works like it, by displaying multiple forms of documentation.

“One of the main premises of the retrospective,” Young explains, “is to present a survey of the past 30 years of the artist’s work, exploring the range of material and scale that she employs, and within that to demonstrate the relationship between her many public projects and the distinct bodies of work that develop from them.

“There’s a space before you go in the exhibition where we’ll have the film documentary about House playing all the time; we’ll have photographs by John Davies of House; and then we’ll have maquettes, images and texts about each major public project.” The work, in each case, becomes something new, composed of the remnants left behind.

“In the early works, she talks a lot about finding mattresses in the streets of East London, and having to wrestle them home — these horrible, sweaty, piss-stained, gross objects which she would then cast.”

“One of the things I love about Rachel,” Young continues, “is that you look at the work and you think you know it; you think about minimalism, and it having this austere quality, you think you’ve got it pegged.

“But actually, what I’ve discovered, doing research, writing for the catalogue and spending time with it, is that the work isn’t perfect or restrained— it’s really intense. Also, how physical it is! In the early works, she talks a lot about finding mattresses in the streets of East London, and having to wrestle them home — these horrible, sweaty, piss-stained, gross objects which she would then cast. Which is not, I think, what you imagine when you think of Rachel Whiteread.”

Indeed, it’s not. But Whiteread often defies preconceptions around herself and her work. Take her drawings — which you might expect to be ideas and sketches for her sculptural works, or precise plans for creating them. For Whiteread, though, a drawing doesn’t need to be limited to marks made on paper; she considers the objects that she finds and collects, and the postcards she’s accumulated from around the world, to be forms of drawing also. They are delicate and intimate works of their own, related to her larger works but also distinct pieces in themselves.

Seven years ago, Tate Britain celebrated these smaller works with the dedicated exhibition Rachel Whiteread Drawings: this autumn, they will return as part of the museum’s full retrospective, shown alongside the iconic, monumental pieces Whiteread has created over the past thirty years.

One of her most well-known works, 2003’s aptly- titled Monument, reflects on the fundamental notion of monumentality itself. Created for the Fourth Plinth in Trafalgar Square, and created using a giant resin cast, the sculpture was a transparent, inverted replica of the plinth it was placed on.

By creating a mirror image, she drew people’s attention to the plinth itself; an architectural feature that forms an integral part of Trafalgar Square, consistently overlooked in favour of what is featured above it — a literal reflection of the place an object occupies, causing us to see that place from a new perspective.

Whiteread has had a long, intimate relationship with London, particularly with the city’s East End. But over the years she has created works rooted in vastly different places. In each instance, she interrogates the history and cultural associations of that specific context, creating works that are always distinctly her own, whilst adapting to fit in to their individual surroundings.

Last year, Whiteread unveiled two new works on opposite sides of the world — both connected by ideas of quietness, and serendipitous discovery. Cabin casts an old wooden shed on Governors Island in New York Harbour. The Gran Boathouse, meanwhile, is the cast of a boathouse on the banks of a remote Norwegian lake. Intended to be ‘quiet sculptures’, they require a degree of effort and planning to visit (or, in an ideal world, would be happily stumbled upon.)

Despite their similarities, the pieces adapt to their respective sites perfectly — Boathouse’fitting seamlessly alongside the other boathouses in its rural landscape, whilst Cabin quietly and reverently looks across New York Harbour to the Statue of Liberty. Initially asked to create a memorial on the World Trade Center site, Whiteread felt that the humble Cabin would be a more appropriate memorial; “I tried to imagine that one could sit there with some kind of dignity,” she reflected, “to create a place of remembrance.”

The nature of Whiteread’s work seems uniquely suited to addressing loss. The casting of the space around objects immediately makes one reflect on the object that once held that space — its absence marked by the gaps and traces it leaves. Whiteread explored loss on a very personal level in 2005 with Embankment, created for the Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall. The piece was comprised of thousands of white polyethylene blocks, cast from found cardboard boxes and stacked upon each other to create a maze-like installation. The inspiration came from an old box Whiteread found when she was going through her late mother Patricia Lancaster’s belongings (Lancaster, also an artist, died in 2003); in the final piece, the boxes all feature the traces and marks of human use.

The impenetrable library makes concrete the immeasurable loss of lives in Austria during the Holocaust, its exposed pages reminding us how it cut short so many stories and personal histories.

But perhaps the most famous of Whiteread’s monuments to loss is 2000’s Judenplatz Holocaust Memorial — more widely known as the Nameless Library. It’s been reported that Whiteread loathed the five year-long, highly bureaucratic process of realising the Viennese memorial. But despite those trials, the piece has become of her most celebrated sculptures.

Public memorials have a difficult task; they need to encourage introspection and reflection, and yet fight against the collective amnesia that often accompanies atrocities while honouring the victims and survivors. Whiteread’s piece is a sombre yet humble structure that maintains this delicate balancing act — the outer surface a cast of bookshelves with all the books turned inwards, so that the pages rather than the spines become visible. The impenetrable library makes concrete the immeasurable loss of lives in Austria during the Holocaust, its exposed pages reminding us how it cut short so many stories and personal histories.

For the Tate Britain retrospective this September, the curators were faced with the challenge of showcasing the breadth of the artist’s work, from delicate drawings to her massive public sculptures.

“One of the most exciting things about this show,” Young enthuses, “is that we’re using 16 rooms in the gallery (which is the entire footprint of the David Hockney show) and we’ve taken out all the walls, so it’s like a football pitch. There’s the beautiful strip-wood floors and white walls and the ceiling — there will be a lot of daylight in this show. “The works will all be in that space, so you’ll go from really modest objects up to the monumental by crossing a few paces. It will be a really unusual architectural experience.”

Alongside Whiteread’s most iconic pieces, the show will also include never-before-exhibited objects from her back catalogue, and a series of new works — papier-mâché casts of the inside of pre-fabricated sheds, using shredded elements and pieces from the artist’s archive and studio, described by Young as inhabiting a place “somewhere between sculpture and drawing.”

The Tate show will provide a unique opportunity to view the full breadth of Whiteread’s practice in a single place, from that first solo exhibition in 1988 to these new papier-mâché objects. And of course Tate Britain itself, the grand Victorian gallery by the Thames which has been dedicated to British art since 1897, is a fitting venue to celebrate a British artist so closely tied to a sense of place. Whiteread couldn’t have chosen a better location herself.

By Siobhan Keam for ARTICLE